Vyom A. Shah (✉) | 9 July, 2024 | āṣāḍha śukla tṛtīyā

Introduction

The intricacies of Indian poetry that has been written since centuries have not only stretched and broadened with time, but have also catered the vast landscape of verses which can be authored across languages. The delicacies of these poetic expressions have not only been enjoyed by the Saṃskṛta poetries, despite of the fact that most of the works on poetics have been authored in Saṃskṛta. This also stands as evidence that Saṃskṛta connected various languages by acting as a bridge or a medium for defying the basics as well as complexities of poetic expressions which can be tasted in Saṃskṛta itself or any Indian vernacular. Nevertheless, the works of poetics have not only been authored in Saṃskṛta, but also in Prākṛta and are being written in modern-day languages like Hindī. The rules or the suggestions devised in these texts and the writing cultures that developed along are the fruits which can be implemented and enjoyed across languages. Just like the Latin macaronic poetry which consists of verses which has an element of other language encompassed within, the Indian poetry witnessed similar (or maybe more intricate) art of generating a tapestry which never fails to amuse its readers in various ways.

A phenomenon of verse embodying more than one language within itself is termed as Bhāṣāsama by later rhetoricians around 14th century, but such poetries have always been a part of literature as well as works on poetics. This is often referred as Bhāṣāśleṣa by earlier rhetoricians like Rudraṭa, (Dhāreśvara) Bhoja, Hemacandrasūri, etc. Bhoja’s monumental work on poetics – Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa has mentioned this under jāti śabdālaṅkāra-s. One of the earliest definitions of Bhāṣāśleṣa is expounded by Rudraṭa in his work – Kāvyālaṅkāra (9th c. century C. E.):

यस्मिन्नुच्चार्यन्ते सुव्यक्तविविक्तभिन्नभाषाणि।

वाक्यानि यावदर्थं भाषाश्लेषः स विज्ञेयः॥४।१०॥

When one clearly speaks sentences in distinct & different languages in same verse, it is regarded as Bhāṣāśleṣa, as far as it depicts a meaning.

Just because the earliest definition available is by Rudraṭa, it doesn’t show the portray a complete absence of such poetry before his times. A few verses in Ānandavardhana’s Devīśataka (quoted by Mammaṭa in Kāvyaprakāśa) and Haribhadra’s Saṃsāradāvanala (which we will see further in this write-up) - one of the most famous Jaina eulogies are the earliest known illustrations of this kind. Rudraṭa also defines bhāṣāśleṣa in a different manner where he mentions that when in a verse, the language of verse is switched between its halves, it is also known as bhāṣaśleṣa (which incidentally matches that what macaronic poetry stands for prominently in Latin and English poetics). He defines the other way around as follows –

वाक्ये यत्रैकस्मिन्ननेकभाषानिबन्धनं क्रियते।

अयमपरो विद्वद्भिर्भाषाश्लेषोऽत्र विज्ञेयः॥४।१६॥

When in a single sentence, a number of languages are incorporated, then this shall also be termed as bhāṣāśleṣa by the learneds.

Types of Bhāṣāśleṣa

- Based on combination of languages

This kind of bhāṣāśleṣa is divided based on the distinction of languages employed in the various. We majorly find combinations of following six:- Saṃskṛta

- Prākṛta (or Mahārāṣṭrī)

- Māgadhī

- Śaurasenī

- Paiśācī

- Apabhraṃśa

These are not limited to only Prākṛta languages. We see such bhāṣāśleṣa poetry in combination Telugu and Saṃskṛta as well.

- Based on meaning

This division comes into picture in the case if the verses, composed in different languages with same words, means same or different. For eg., a verse from Devīśatakam (quoted by Mammaṭa, Hemacandrasūri and Viśvanātha) can be read in both Saṃskṛta and Prākṛta and it would mean different in both languages.

When the verse means the same in both languages, it is also an instance of bhāṣāśleṣa only.

Here, we shall first discuss the later one. It is an instance when the meanings of the verse, united by same syllables in same order and yet divided by language, bridged by poetic intricacies, tend to mean the same.

Why is it a big deal?

It is always a matter of curiosity how the poet authored with such an art which we will discuss here-upon. Here, I shall first explain in regard of Prākṛta (general or Mahārāṣṭrī) as its illustrations are prominently encountered.

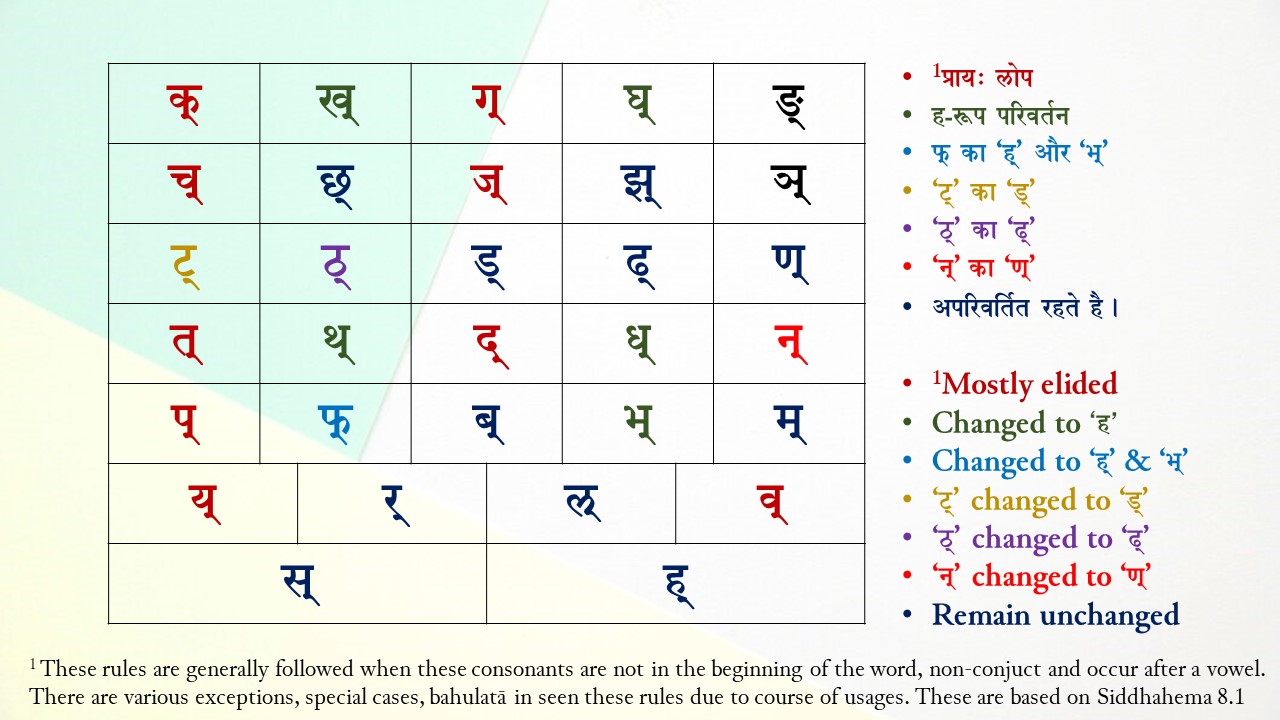

Not all the consonants or vowels can be used in Prākṛta as we use in Saṃskṛta. See following chart for instance.

Similar, no two non-homogenous consonants can be together. Thus, we see surd (hard, aghoṣa) unaspirated in conjuncts with themselves or surd aspirated only. Same is seen with non-surd (soft, ghoṣavat) unaspirated and aspirated. The nasal consonants can be conjuncts with their class of consonants. The sibilants are not seen in conjuncts. The semi-vowels are seen as conjunct with themselves only. There are a few occurrences where non-homogenous consonants are seen in conjuncts, for instance, dr (similar to Saṃskṛta), ṇh, mh, lh, etc. (very rare found in Saṃskṛta).

In the case of vowels, there are only 8 of them in Prākṛta – a, ā, i, ī, u, ū, e, and o. There are no pluta vowels, however nasal vowels (anunāsika svara) are more oftenly used.

There are no visarga, jihvāmūlīya or upadhmānīya in Prākṛta and there are very few places where nominal forms or verbal forms would seem parallel to Saṃskṛta (for instance, 5 {or 6 with sandhi} suffixes in Prākṛta’s laṭ-lakāra may appear same as Saṃskṛta under specific conditions).

Though, it might seem that Saṃskṛta and Prākṛta would rarely come on same page, the poets have found amusing ways extending the extent of application of rules in Prākṛta and also at the same time, making the Saṃskṛta form with sandhi, et al., such that same formation coexists in Prākṛta.

A 7th century illustration

Let us see an example of a eulogy of Jina from a 7th century Jaina monk – Haribhadrasūri –

संसारदावानलदाहनीरं संमोहधूलीहरणे समीरम्।

मायारसादारणसारसीरं नमामि वीरं गिरिसारधीरम्॥१

भावावनामसुरदानवमानवेन चूलाविलोलकमलावलिमालितानि।

संपूरिताभिनतलोकसमीहितानि कामं नमामि जनराजपदानि तानि॥२

बोधागाधं सुपदपदवीनीरपूराभिरामं जीवाहिंसाऽविरललहरीसंगमागाहदेहम्।

चूलावेलं गुरुगममणीसंकुलं दूरपारं सारं वीरागमजलनिधिं सादरं साधु सेवे॥३

आमूलालोलधूलिबहुलपरिमलालीढलोलालिमाला-झङ्कारारावसारामलदलकमलागारभूमिनिवासे!।

छायासंभारसारे! वरकमलकरे! तारहाराभिरामे! वाणि! संदोहदेहे! भवविरहवरं देहि मे देवि सारम्॥४

This is a very famous eulogy among Śvetāmbara Jainas and is recited during every fortnightly prarikramaṇa (on caturdaśī).

By giving a closer look these verses, one can know how the poets tend to stay away from conjuncts. The only combination of conjuncts we see here is nasal consonants with their respective class of consonants. Similarly, they have used ‘r’ 41 times, ‘l’ 33, ‘s’ 25 times, and ‘m’ 27 times times which prominently remain common Saṃskṛta and Prākṛta. One might notice ‘dh’, etc., have not been changed to 'h'which is because ‘dh’ in beginning of a successive word within a compound can be treated like a syllable in the beginning. Same is to be understood for others. For occurrences of ‘dh’ within the words, it shall be understood as a characteristic of ārṣa Prākṛta discussed at length by A.F. Rudolf Hoernle in his introduction to “Chanda’s Grammar of the Ancient Prākṛit”. The preservation of medial ‘t’ is also due to course of ārṣa Prākṛta only. For the question regarding ‘seve’, it is a siddha Saṃskṛta word directly used in Prākṛta. This practice is not alien to Prākṛta and is evident through its various usages at many places.

These are the ways employed by poets to create the ‘magic’! Astonishingly, each of these four verses mean the same in both Saṃskṛta and Prakṛta.

Another instance

Let us take another instance from Devīśataka by Ānandavardhana:

महदेसुरसन्धम्मे तमवसमासङ्गमागमाहरणे।

हरबहुसरणं तं चित्तमोहमवसरेउमे सहसा॥

In this verse, the poet has used both Saṃskṛta and Prākṛta in praise of Devī such that it has meaning changes as we switch languages. The meanings can be read here.

Through a preliminary examination, it seems that bhāṣāśleṣa started to be employed around 6th-7th century which received a welcome from the rhetoricians as well as poets. One of the earliest usages in classical literature is from 8th century Saṃskṛta poet Bhavabhūti’s drama – Mālatīmādhavam where the male protagonist Mādhava speaks a dialogue (6.10) in Saṃskṛta which is understood by his beloved Mālatī as Prākṛta. This verse meant completely same in both languages. Thus, with time, this might have been added to the prescriptive and descriptive works, oldest of all being the Rudraṭa’s Kāvyālaṅkāra (9th century C. E.), then Bhoja’s Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa and Śṛṅgāra-Prakāśa (10th century), Mammatā’s Kāvyaprakāśa (11th century), Hemacandrasūri’s Kāvyānuśāsana (11th century), and Viśvanātha’s Sāhityadarpaṇa (14th century) and so on.

In next blog, I will be discussing upon verses where language is switched at halves.

Bibliography:

1. Bhojadeva's Sarasvatīkāṇṭhābharaṇa, With commentaries by Rāmasiṃha and Jagaddhara, Ed. by Kedārnātha Śarmā and Vāsudev Lakṣmaṇ Śāstrī, Nirnay Sagar, 1934 (2nd Ed.)

2. Rudraṭa's Kāvyālaṅkāra with commentary by Namisādhu, Ed. by Kedārnātha Śarmā and Vāsudev Lakṣmaṇ Śāstrī, Nirnay Sagar.

3. Hemacandrasūri's Kāvyānuśāsana with auto-commentary 'alaṅkāracūḍāmani' and 'viveka', Ed. by Rasiklāl Parīkh, Mahavīra Jain Vidyālaya, 1938

4. Viśvanātha's Sāhityadarpaṇa with Hindi commentary by Śālagrāma Vidyāvācaspati, Bhāratīya Kalā Prakāśāna, 2008

5. Bhaṭṭikāvya of Bhaṭṭi, With the Commentary Jayamangalā of Jayamangala. Ed. by The Late Vināyak Nārāyan Shāstrī Joshi; V.L. Shāstrī Paṇśīkar. Bombay, 1934 (8e éd.).

6. HAHN, Michael. Śivasvāmin's Kapphiṇābhyudaya, edited by M. Hahn with preface in English. Sanskrit text, selected variant readings, index of verses and five appendices. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 2013

7. Pañcapratikramaṇa, Ed. by Pt. Sukhalāl, Ātmārām Jain Pustak Prakāśan Maṇḍal, Āgrā, 1921